PiDP-1 Rack version

PiDP-1 Console version

The PDP-1 was the first computer made by DEC - Digital Equipment Corporation, based on MIT's TX-0 and TX-2 experimental computers.

Its history is told very well on Wikipedia. A team at the CHM has restored one PDP-1 to working order; and Angelo Papenhoff has written exact simulators in both Verilog and C - including the Type 30 display. Our replica is based on this simulator.

Three years ago, we started work on a replica, to complete the PiDP series (-8, -10, -11). Little did we know that this adorable dinosaur would become our favourite of the whole range. The PDP-1 is a truly fun machine to work and play with - and so, this text turned out a bit less formal than the other machines' pages.

The PDP-1 was a first in many respects. But it is also simple enough to be quickly understandable to any 21st century computer user. It remains the original Hacker's machine. - the word comes from the

hacker community forming around the PDP-1 at MIT; their demo programs are still attractive eye candy thanks to the Type 30 display. Which was a converted radar display.

Driving the electron beam over its phosphor, you can get very pretty graphics effects from only a little bit of simple programming. But serious programs were also written, despite the minimal resources of the machine it spawned the first-ever text editors, a sensational Lisp, and FORTRAN. Even the first interactive multi-user system software. Much of this has been preserved and brought to run again.

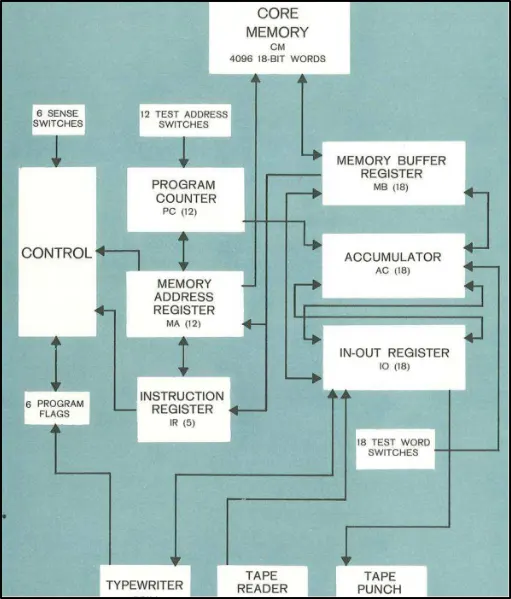

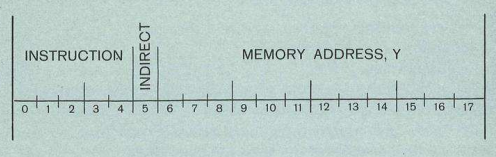

Exactly because of its simplicity, this is the machine we'd really want to learn assembly language on. Before you laugh, let us give an overview of the machine from three different perspectives. Forgive us for such frivolity with a historical machine.

So we'd like to describe the machine in these three steps, violating historical correctness but focusing on why we love the One. Of all the pre-home computer systems we played with over the years, this is the most fun. Look at it as the first games console, then as the first democoder platform, and then read about the Serious Work that was done on this historical computer. It deserves to live on in the 21st century as the 'original retrogaming/democoding computer'. Just a few dozen lines of surprisingly friendly assembly give pretty cool graphics on the radar tube, and we want to show you!

The first games console

You would think it is a bit of a stretch to call a $100,000 computer from 1959 a games console. Because its compact front panel (and its spacewar games controllers, there's another historical first) were attached to the side of a row of four racks full of electronics, because it weighed 1200 pounds. Yet, it is not a stretch. Its main claim to fame was after all the spacewar video game, written by students and research assistants, and used everywhere as the ultimate demo of what the machine could do. It had a 1024*1024 converted radar display tube, plotting up to 20,000 X/Y points per second on the phosphor, fading away in about that time if the display was not redrawn the next second again.

The One has seen a revival in interest in the past decade, with new games still being written for the machine. And it is easy to see why, as steering the electron beam from point to point is a fun, algorithmic, way of doing computer graphics. The fading phosphor also gives a special, very atmospheric effect to the dozen or so graphics demo programs written for the machine.

So - were it not for the fact that the $1 integrated circuit was not invented yet, this machine would have been in every teenager's bedroom playing games. We are quite serious. Alas, it remained the privilege of a select few students and scientists to play with the One. Only 53 were ever made. But it did spark off the tremendous development in computer power. Digital Equipment Corporation would be the second-largest computer manufacturer 20 years later, employing 130,000 people at its peak. Alas - only to be crushed by the microprocessor revolution only a few years later.

https://youtu.be/yZPhj-CKH3Y

The original democoder machine

Actually, the PDP-1 was tiny enough so that it could not do too many things. Elegant, mean and lean graphics demos were thus a natural application for it. And that's not a trivial contribution to computing; a lot of graphics algorithms were invented here. And to quite some extent, the whole notion of interactive graphics. It helped anourmously that the PDP-1 was one of the first (arguably, the first) interactive computers. Meant to be used with input from a keyboard, entering into a dialogue with its one single user. Not pumped with a stack of punch cards, running until the output was dumped on a line printer.

But the PDP-1 became the birthplace of democoding for two more reasons. The first was that DEC, historically close to MIT, was quite happy to put an early machine in the hands of MIT students. It ended up running a model railroad; someone invented the idea of a computer video game; people visually explored chaos and order emerging from math formulas. The second reason was that this was a machine that was actually designed to be fun to operate. Not only was it interactive, its instruction set was concise, easy to learn, and the software tools (editor, assembler) quickly emerged to make the life of a coder a good one. And so, the Hacker Ethos emerged here (*).

(*) The book Hackers by Stephen Levy (link to the free chapters) is a true must-read if you have not already done so. It gives a very atmospheric background story to the Origin Of Hackerdom.

A Milestone in Computer History

Not just because it spawned the second-largest computer company within a few short years, and not just because the PDP range of computers drove computer evolution for the next 25 years. Also, because so many now-obvious ideas were born on the One itself. The idea of a text editor (teco). The idea of an interactive debugger (ddt). And, bizarrely given the tiny size of the machine: timesharing. In other words, letting multiple users run multiple programs interactively, behind their keyboards. It only worked because the attached drum storage was fast enough to swap the entire 4kW of memory to drum in 20 milliseconds.

Through the work of many people, with honourable mention of Al Kossow first, tons of software and documentation has been preserved. Alas, not everything - the first text editor has been lost. But a high school student wrote a Lisp interpreter for the machine - along the way, coming up with the REPL concept too. The truly determined could write Fortran code as well, but assembly remained the preferred language for most. Helped by the nice instruction set, and the interactive debugger. A luxury that is hard to appreciate from today's point of view. Until you try to work without it first. The difference needs to be experienced...

We should mention one more Milestone in the Life of The One. Arpanet. Most written histories of the internet and its origin begin with the mainframes connected to it. But in fact, the software for the IMP Arpanet routers was written with a cross-compiler on a PDP-1. In only nine months. It says smething about the PDP-1: Eight years after it came out, outdated as it was, it performed this epic task of software development. Not only that, the PDP-1 was then usefully employed to send online updates to the IMP routers in the field (which was another first, remote software updates) and acted as the network's real-time monitor, checking for downtime and problems with the Arpanet routers.

So - yes. The first games console in history; the first democoding platform; and more than 12 years later a PDP-1 still manages the earliest incarnation of the internet. Adorable machines can do astonishing things if they're well coded for.

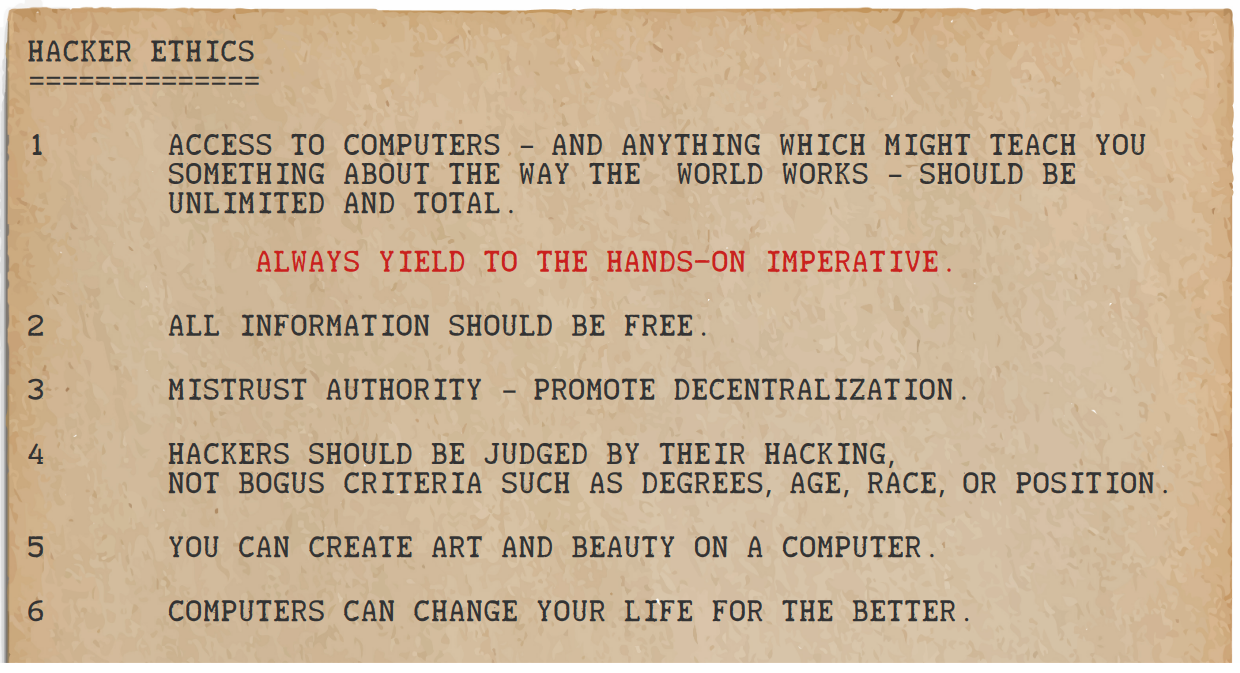

The Hacker Ethic as first formulated by the MIT PDP-1 hackers.

The Hacker Ethic as first formulated by the MIT PDP-1 hackers.

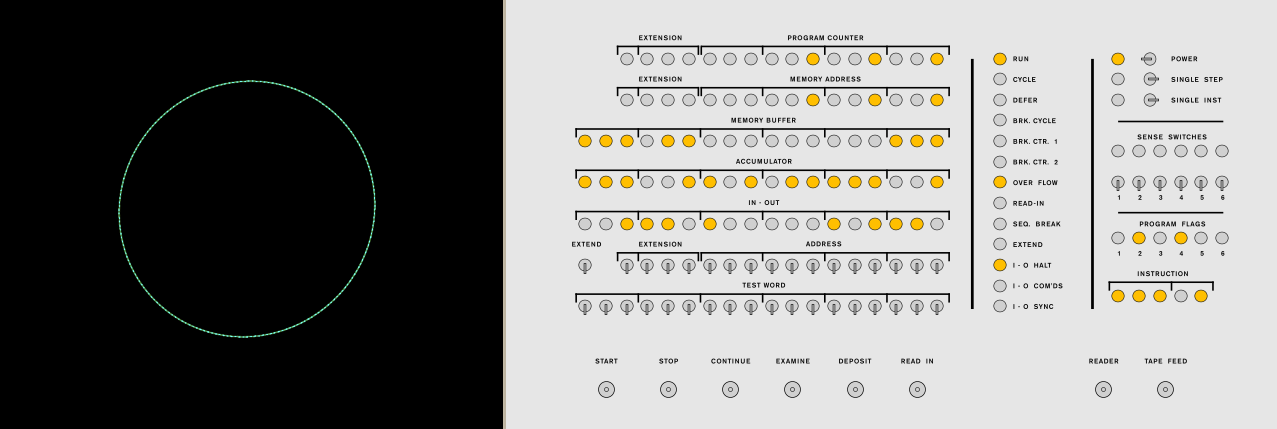

We throw in an image of the PDP-1 Blinkenlights - it's operating the front panel that makes coding the PDP-1 fun.

We throw in an image of the PDP-1 Blinkenlights - it's operating the front panel that makes coding the PDP-1 fun.